COULD OWL AND CROCODILIAN TEARS LEAD TO A CURE FOR YOUR DRY EYES?

Dr. Arianne Pontes Oriá stands firm: She does not make animals cry for a living.

Technically, only humans can cry, or weep in response to an emotional state, said Dr. Oriá, a veterinarian at the Federal University of Bahia in Brazil. For humans, crying is a way to physically manifest feelings, which are difficult to study and confirm in other creatures.

But Dr. Oriá does collect animal tears — the liquid that keeps eyes clean and nourished. In vertebrates, or animals with backbones, tears are vital for vision, Dr. Oriá said. And yet, these captivating fluids have been paid little to no attention, except in a select few mammals.

“A lot of vision, we’re not aware of until it’s a problem,” said Sebastian Echeverri, a biologist who studies animal vision but doesn’t work with Dr. Oriá’s team. “We notice when tears are missing.”

That’s a bit of a shame, Dr. Oriá said. Because whether it hails from dogs, parrots or tortoises, the stuff that seeps out of animals’ eyes is simply “fascinating,” she said.

As she and her colleagues have reported in a series of recent papers, including one published on Thursday in the journal Frontiers in Veterinary Science, tears can be great equalizers: Across several branches of the tree of life, vertebrates seem to swaddle their eyes with fluid in much the same way. But to help them cope with the challenges of various environments, evolution has tinkered with the tears of the world’s creatures in ways that scientists are only beginning to explore. Research like Dr. Oriá’s could offer a glimpse into the myriad paths

that eyes have taken to maximize their health and the well-being of the organisms that use them.

Given how often eye problems can plague humans and other animals, there’s “a lot to be learned from these adaptations,” said Dr. Sara Thomasy, a veterinary ophthalmologist at the University of California, Davis, who wasn’t involved in Dr. Oriá’s studies.

Dr. Oriá began her research by studying the tears of caimans, which have “a very curious ocular surface,” she said. While humans blink about 15 times a minute, helping spread fresh-squeezed tears over the cornea, caimans can go about two hours without batting an eyelid (of which they have three). But their eyes don’t dry out.

“We started to think, ʻWhat kind of molecules give these tear films stability?’ It’s amazing,” Dr. Oriá said. The answer, she added, could aid the development of treatments for dry eyes and other ophthalmic troubles in people.

In the years that followed, her team’s list of tear donors has expanded to include other reptiles such as turtles and tortoises, as well as hawks, parrots, owls and other birds. (Dr. Oriá and her colleagues have also added mammals like humans, dogs and horses for the sake of comparison.)

Across animals, the collection process is mostly the same: During a routine veterinary exam, a human researcher will gently restrain the creature, wait for it to relax and then dab carefully at its eye with a strip of absorptive paper.

This isn’t always easy. Researchers must take extra care to be gentle with the animals, which don’t always shed as many tears as they would like. Some species are even fussier at eye exams than people are. Macaws apparently “hate to be restrained after lunch,” Dr. Oriá said.

But the entire process comes down to what’s best for the patients. Whatever tears they’re willing to offer, Dr. Oriá said, “we respect that, even if it is only a tiny amount.”

The trouble doesn’t end with collection. One of her group’s recent projects involved shipping the tears of more than 100 caimans from Brazil to a collaborator’s lab at the University of California, Davis. Perplexed by its contents, customs agents delayed the package in transit. The samples degraded at room temperature, and Dr. Oriá and her team had to start the collection process over. Things worked out better the second time, she said.

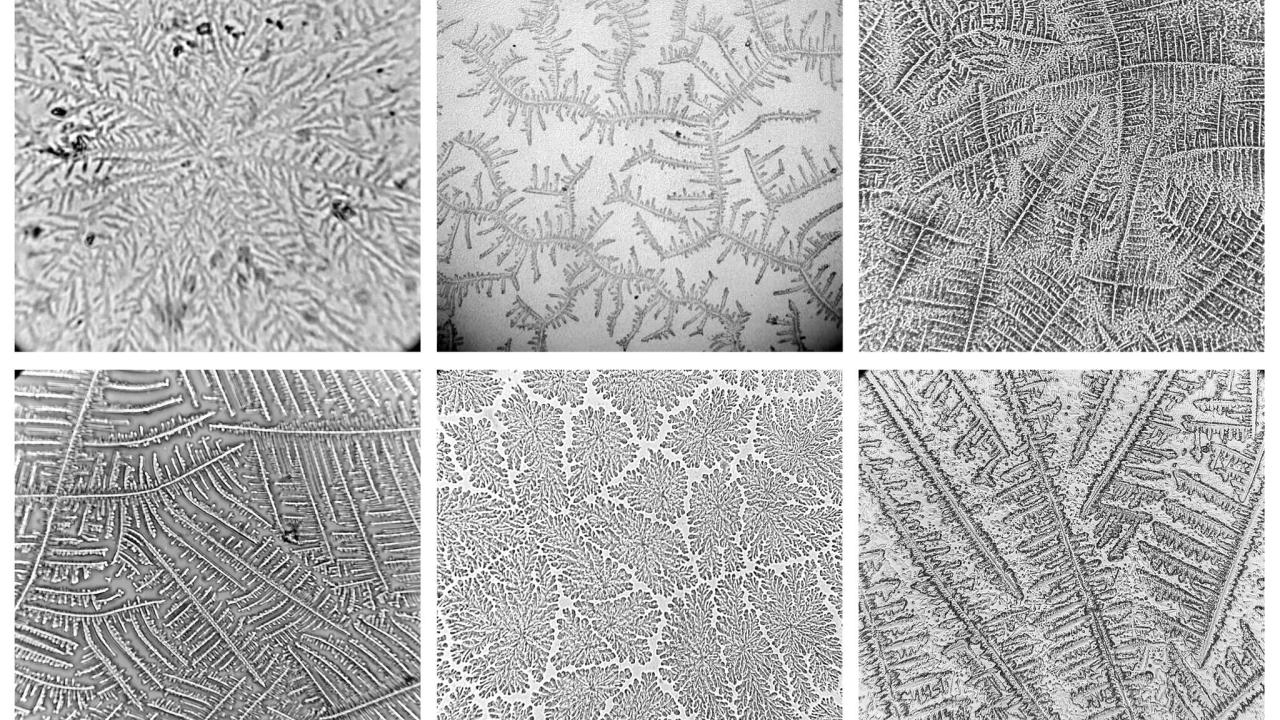

It still isn’t totally clear what’s responsible for the staying power of caiman tears. But Dr. Oriá’s team has gleaned a few hints from the crystal patterns that the liquids leave behind after they dry, each as unique as a snowflake. These patterns, when visualized under a microscope, can differ vastly among species.

“It is one of the most beautiful things that you can see,” Dr. Oriá said.

Dried caiman tears, she added, form thicker lattices than those from some other animals, possibly making them more stable.

By and large, though, the chemical recipe for tears, which include a slurry of water, fats, proteins and charged minerals such as sodium, seems to be pretty similar across various species. The few variations that exist seem to track with habitat, the researchers found. Animals that spent most of their time on land, for instance, had more proteins in their tears than their seafaring counterparts, but they also had less

urea — a molecular waste product that’s also found in urine.

Dr. Oriá’s team also previously found chemical similarities among dog, horse and human tears, all of which seem to flow quite freely. That might be a mammal thing, Dr. Oriá said. But perhaps domestication, which prompted a big shift in scenery for these previously wild animals, tamed their tears, too.

That an animal’s surroundings heavily influence the composition of tears, which are constantly exposed to the outside world, “makes a lot of sense,” Dr. Echeverri said. “Most of our other liquids are waste that we get rid of, or internal. Tears have to deal with the environment from moment to moment.” (But tears aren’t universal, Dr. Echeverri noted. Invertebrates, which have very different body plans, have had to concoct tear-free methods of keeping their eyes clean. Some spiders, for instance, use bristle-like hairs on their legs to brush away dust and debris.)

Some of the weirdest tears out there, Dr. Oriá said, come from loggerhead sea turtles, whose eyes secrete fluids so viscous they are practically sap — and impossible to collect with the supplies she and her students typically use to sop up specimens. “We tried paper strips, we tried micropipettes, nothing,” she said. “The mucus stuck in everything.”

They finally worked out a method of sucking up the sludge with a superstrong syringe.

Dr. Thomasy suspects the tears’ texture helps them stick to the eyeballs of loggerhead sea turtles, even when they’re underwater. On land, though, it makes for quite the spectacle. “I would guess it would look like the worst snot you’ve ever seen,” she said.

But Dr. Oriá doesn’t mind the turtle gloop.

“It’s fun, it’s like an adventure,” she said. “I forget all my problems when I am dealing with these animals.”

Katherine J. Wu is a reporter covering science and health. She holds a Ph.D. in microbiology and immunobiology from Harvard University. @KatherineJWu